Function Arguments

Next comes one (monadic), followed closely by two (dyadic).

Three arguments (triadic) should be avoided where possible.

More than three (polyadic) requires very special justification—and then shouldn't be used anyway.

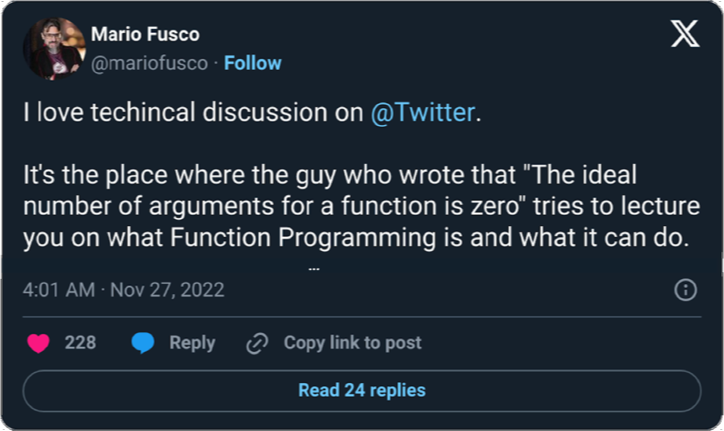

I think Robert Martin gets the most amount of hate for this one.

The main problem with Martin's advice: it presents itself as "less is better" but handwaves all the downsides of the particular application. He ignores trade-offs and side effects.

- "Smaller methods are better", but the increased amount of methods? Nah, you'll be fine.

- "Less arguments for a function is better", but the increased scope of mutable state? Nah, you'll be fine

- "Compression is better", but the bulging discs? Nah, you'll be fine.

One particularly odd suggestion is to "simplify" by moving arguments into instance state:

StringBuffer in the example. We could have passed it around as an argument rather than making it an instance variable,

but then our readers would have had to interpret it each time they saw it.

When you are reading the story told by the module, includeSetupPage() is easier to understand than includeSetupPageInto(newPageContent)

This doesn't eliminate complexity - it relocates it. But worse: moving parameters to fields increases size and the scope of the mutable state of the application. This sacrifices global complexity to reduce local one. Tracking shared mutable state in multi-threaded environments is far harder than understanding function arguments.

But this just shifts the burden. Method calls become simpler, but setting up test instances and tracking state becomes harder. Not a winning trade.

Ironically, functional programming exists specifically to limit mutable state, recognizing its cognitive cost. Martin clearly wasn't a fan at the time of writing Clean Code.

Beating the same dead horse: render(pageData) might be easy to understand. SetupTeardownIncluder.render(pageData) still doesn't make sense.

Flag Arguments

Martin’s critique of flag arguments is front-loaded with emotion, but is it valid?

Adding boolean or any parameter is indeed a complication. Since boolean can accept 2 states, speaking more formaly adding boolean is doubling the domain space of the function.

Adding a boolean parameter to a function that already has 2 booleans will bring domain space from 4 to 8, this might be significant. But adding boolean argument to a function that had none before would not kick complexity level into "unmanagable" territorry. It might be a tolerable increase.

While render(true) is indeed unclear on a caller side, modern programming languages offer solutions, such as named parameters:

render(asSuite = true) # costs nothing in runtime

The deeper problem with render(true) is so-called boolean blindness

from Boolean Blindness

A better solution: Use enums to preserve semantic meaning:

enum ExcutionUnit {

SingleTest,

Suite

}

//...

public String renderAs(ExecutionUnit executionUnit) { ... }

// ------

//calling side:

renderAs(ExeuctionUnit.Suite);

It's unclear if Robert Martin likes enums.

The inherit unavoidable complexity is that tests can have 2 execution types: as a single test or as a part of a suite.

Splitting the render function "into two: renderForSuite() and renderForSingleTest()" does not reduce it. (neither does using boolean or enum)

It is still 2 types of execution.

There will be place in code that would have to take a decision and select one of the branches.

Please do not create Abstract Factory for every boolean in your code.

Verbs and Keywords

For example, assertEquals might be better written as

assertExpectedEqualsActual(expected, actual)The suggestion to encode order of parameters in the name is not scalable - it works in isolation, but would degrate quickly with real API when you need to do all kind of assertions:

assertExpectesIsGreaterOrEqualsThanActualassertActualContainsAllTheSameElementsAsExpected

The best solution java can offer is fluent API: AssertJ

assertThat(frodo.getName()).isEqualTo("Frodo");

Outside java, this problem has other solutions:

- Named parameters - In languages like Python, named parameters eliminate ambiguity:

assertEquals(expected = something, actual = actual)

- Macros - In Rust, macros like assert_eq! automatically capture and display argument details, making order irrelevant:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[test] fn test_string_eq() { let expected = String::from("hello"); let actual = String::from("world"); assert_eq!(expected, actual); // Error message: // thread 'test_string_eq' panicked at: // assertion `left == right` failed // left: "hello" // right: "world" // at src/main.rs:17:5 } }