Review of "Clean Code" Second Edition

This is true! Clean Code’s second edition is pretty much the same: same tiny-functions style, the same old OOP habit of mixing data and behavior into choppy class designs, and the same blind spots.

I wrote a critique of Clean Code's first edition and was curious how much of it would become obsolete. After reading it, the answer is: "not much, if anything"

It is a different book in some ways:

- The first edition was focused, concise and highly opinionated. You could disagree with 80% of it and still appreciate it as a clear, coherent message about one particular style of programming.

- The second edition is less focused. It’s an amalgamation of Martin’s work - a collage of Clean Code, The Clean Coder, Clean Architecture, We Programmers, and SOLID material.

It’s also a noticeably thicker book - full of digressions, rants, and good old rambling.

But the code part has not really changed. This review focuses on "Part 1: Code".

...

Here's a good example of the new format:

In Chapter 10 - "One Thing" - he addresses critiques of his style of tiny functions:

-

People are afraid that if they follow this rule, they will drown beneath a sea of tiny little functions.

-

People are afraid that following this rule will obscure the intent of a function because they won't be able to see it all in one place.

-

People worry that the performance penalty of calling all those tiny little functions will cause their applications to run like molasses in the wintertime.

-

People think they're going to have to be bouncing around, from function to function, in order to understand anything.

-

People are concerned that the resulting functions will be too entangled to understand in isolation.

Let's address these one at a time.

- Drowning

Long ago our languages were very primitive. The first version of Fortran, for example, allowed you to write one function. And it wasn't called a function. It was just called a program. There were no modules, no functions, and no subroutines. As I said, it was primitive.

COBOL wasn't much better. You could jump around from one paragraph to the next using a goto statement; but the idea of functions that you could call with arguments was still a decade in the future.

When Algol, and later, C, came along, the idea of functions burst upon us like a wave. Suddenly we could create modules that could be individually compiled. Modular programming became all the rage.

But as the years went by, and our programs got larger and larger, we began to realize that functions weren't enough. Our names started to collide. We were having trouble keeping them unique. And we really didn't like the idea of prefixing every name with the name of its module. I mean, nobody likes io_files_open as a function name.

So we added classes and namespaces to our languages. These gave us lovely little cubbyholes that had names into which we could place our functions and our variables. Moreover, these namespaces and classes quickly became hierarchical. We could have functions within namespaces that were within yet other namespaces.

He keeps going, but you can see that:

- Points 1, 2, and 4 are essentially the same concern.

- Folksy phrasing like “run like molasses in the wintertime” doesn’t clarify anything.

- Instead of addressing the core critique, he detours into a thin language-history lesson.

This is the style of the second edition.

What has somewhat improved is the Java code: most examples in the first edition were abysmally bad, and while the second edition is better, it still leaves much to be desired.

The second edition has examples in other languages. But Martin writes Python and Go as if they were Java with disclaimers that he doesn’t really know them:

- "It’s been a long time since I’ve written any Python, so bear with me."

- "I apologize - I am not an accomplished Golang programmer"

Why does he use them? I guess to prove that the ideas aren’t Java-specific and apply across languages. And they might be - if you write Java in Python. Do they apply if you write Python in Python? That’s left as an exercise for the reader.

Over the years Martin has definitely heard the critique of his original book, and he has participated in debates around it (with Casey Muratori about performance, and with John Ousterhout about style and design).

I don't believe Martin internalized the critique or revised any of his recommendations.

There is a tonal shift here and there towards being more accepting of alternative views ("but you may disagree. That's OK. We are allowed to disagree. There is no single standard for what cleanliness is. This is mine, and mine may not be yours."), but I haven't noticed any changes in the way he writes code.

Chapter 2 - Clean that code!

This chapter is a replacement for "Chapter 14: Successive Refinement" from the first edition.

This is a good illustration that it's the same "Clean Code"(tm) style from 2007 - nothing has really changed.

As a reminder:

- Avoid comments. Over-use "description as a name" instead

- Extract a lot of tiny functions that are used only once

- Move parameters to class state and pass them implicitly from everywhere to everywhere

This is how he cleans the code in 2024: Original version on the left; the cleaned-up version on the right:

package fromRoman;

import java.util.Arrays;

public class FromRoman {

public static int convert(String roman) {

if (roman.contains("VIV") ||

roman.contains("IVI") ||

roman.contains("IXI") ||

roman.contains("LXL") ||

roman.contains("XLX") ||

roman.contains("XCX") ||

roman.contains("DCD") ||

roman.contains("CDC") ||

roman.contains("MCM")) {

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

roman = roman.replace("IV", "4");

roman = roman.replace("IX", "9");

roman = roman.replace("XL", "F");

roman = roman.replace("XC", "N");

roman = roman.replace("CD", "G");

roman = roman.replace("CM", "O");

if (roman.contains("IIII") ||

roman.contains("VV") ||

roman.contains("XXXX") ||

roman.contains("LL") ||

roman.contains("CCCC") ||

roman.contains("DD") ||

roman.contains("MMMM")) {

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

int[] numbers = new int[roman.length()];

int i = 0;

for (char digit : roman.toCharArray()) {

switch (digit) {

case 'I' -> numbers[i] = 1;

case 'V' -> numbers[i] = 5;

case 'X' -> numbers[i] = 10;

case 'L' -> numbers[i] = 50;

case 'C' -> numbers[i] = 100;

case 'D' -> numbers[i] = 500;

case 'M' -> numbers[i] = 1000;

case '4' -> numbers[i] = 4;

case '9' -> numbers[i] = 9;

case 'F' -> numbers[i] = 40;

case 'N' -> numbers[i] = 90;

case 'G' -> numbers[i] = 400;

case 'O' -> numbers[i] = 900;

default -> throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

i++;

}

int lastDigit = 1000;

for (int number : numbers) {

if (number > lastDigit) {

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

lastDigit = number;

}

return Arrays.stream(numbers).sum();

}

public static

class InvalidRomanNumeralException extends RuntimeException {

public InvalidRomanNumeralException(String roman) {

}

}

}

package fromRoman;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

public class FromRoman {

►private String roman;

private List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<>();

private int charIx;

private char nextChar;

private Integer nextValue;

private Integer value;

private int nchars;this is unfortunate mix of input data, intermediate computation state, and output data

What's surprising is that Martin wants method bodies to be clean, but doesn't mind mess in object's state or class namespace

►Map<Character, Integer> values = Map.of(this should be a constant, i.e. "static private final"

'I', 1,

'V', 5,

'X', 10,

'L', 50,

'C', 100,

'D', 500,

'M', 1000);

►public FromRoman(String roman) {this should be private, if we want `convert` to be an entry point

this.roman = roman;

}

public static int convert(String roman) {

return new FromRoman(roman).doConversion();

}

private int doConversion() {

checkInitialSyntax();

convertLettersToNumbers();

checkNumbersInDecreasingOrder();

return numbers.stream().reduce(0, Integer::sum);

}

private void checkInitialSyntax() {

checkForIllegalPrefixCombinations();

checkForImproperRepetitions();

}

private void checkForIllegalPrefixCombinations() {

►checkForIllegalPatterns(

new String[]{"VIV", "IVI", "IXI", "IXV", "LXL", "XLX",

"XCX", "XCL", "DCD", "CDC", "CMC", "CMD"});useless allocations. these should be extracted into constants

}

►private void checkForImproperRepetitions() {there is no need to split validation in 3 methods. this just pollutes name space

►checkForIllegalPatterns(

new String[]{"IIII", "VV", "XXXX", "LL", "CCCC", "DD", "MMMM"});useless allocations. these should be extracted into constants

}

private void checkForIllegalPatterns(String[] patterns) {

for (String badString : patterns)

if (roman.contains(badString))

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

private void convertLettersToNumbers() {

char[] chars = roman.toCharArray();

nchars = chars.length;

for (charIx = 0; charIx < nchars; charIx++) {

nextChar = isLastChar() ? 0 : chars[charIx + 1];

nextValue = values.get(nextChar);

char thisChar = chars[charIx];

value = values.get(thisChar);

switch (thisChar) {

case 'I' -> addValueConsideringPrefix('V', 'X');

case 'X' -> addValueConsideringPrefix('L', 'C');

case 'C' -> addValueConsideringPrefix('D', 'M');

case 'V', 'L', 'D', 'M' -> numbers.add(value);

default -> throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

}

}

private boolean isLastChar() {

return charIx + 1 == nchars;

}

private void addValueConsideringPrefix(char p1, char p2) {

if (nextChar == p1 || nextChar == p2) {

numbers.add(nextValue - value);

charIx++;

} else numbers.add(value);

}

private void checkNumbersInDecreasingOrder() {

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.size() - 1; i++)

if (numbers.get(i) < numbers.get(i + 1))

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

public static

class InvalidRomanNumeralException extends RuntimeException {

public InvalidRomanNumeralException(String roman) {

super("Invalid Roman numeral: " + roman);

}

}

}

Let's be clear: this is a stylistic choice. It doesn't improve any objective metric.

As a style, it's very recognizable: when you see long-named functions that have 0-1 parameters and very short bodies - you immediately think "Oh. That's Uncle Bob's Clean Code".

From an artistic standpoint, creating a distinctive, instantly recognizable style is an achievement. I bet you know a colleague or two who uses it.

But code isn't art. The question is whether the style helps you build and maintain software.

Putting the style aside for a moment, you'll notice that the "improved" code is surprisingly sloppy:

- Confusing public API: class

FromRomanhas a single public entry point - static methodconvert, this means the constructor should be private.

If we are aiming for code to be new-reader friendly, the proper implementation would be:

// internal constructor. use static method 'convert' instead

private FromRoman(String roman) {

this.roman = roman;

}

- Unnecessary allocations: The immutable values (

Map<Character, Integer> values) have to be "private static final" to avoid creating the same reference data every time you do a conversion. The validation patterns are allocated on each call too.

Here's how it should be done instead:

private static final String[] INVALID_PATTERNS = {

// Illegal prefix combinations

"VIV", "IVI", "IXI", "IXV", "LXL", "XLX",

"XCX", "XCL", "DCD", "CDC", "CMC", "CMD",

// Improper repetitions

"IIII", "VV", "XXXX", "LL", "CCCC", "DD", "MMMM"

};

private static void validate(String roman) {

for (String pattern : INVALID_PATTERNS) {

if (roman.contains(pattern)) {

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

}

}

This eliminates the useless allocations and removes the pointless checkForIllegalPrefixCombinations, checkForImproperRepetitions, and checkForIllegalPatterns helpers.

- It's a smaller code chunk that does exactly the same

- This code is less work for the compiler to compile

- It will perform better at runtime

- It would generate less garbage and have less memory pressure

All for free, just from using a different style.

And let's talk style. Arguably private static void validate(String roman) is an easy-to-understand signature. You don't need to

jump across the code to guess what it is doing. And the implementation utilizes different language constructs to express the intent:

- Inputs for the processing - as method arguments

- Static immutable reference data - as constants

- Code explanation - as comments

In contrast, Clean Code advocates using method names for code explanation and class fields for passing parameters and results. This feels like a misuse of the instrument.

Now try to work out the purpose and relationships between these methods from signatures only:

private void checkForIllegalPrefixCombinations()private void checkInitialSyntax()private void checkForIllegalPatterns(String[] patterns)private void checkForImproperRepetitions()

Fun!

P.S. Sometimes it's worth encoding documentation into the name to make things more visible (for example, runTaskDangerouslySkipPermissions),

but this should not be a go-to move. This is a special case situation that requires justification.

...

This is the moment that made me chuckle:

YES! Everyone finds this annoying! Lean into this feeling! See the light, Robert! It's not too late.

But then he falls into justifications:

This annoyance is an issue that John Ousterhout and I have debated. When you understand an algorithm, the artifacts intended to help you understand it become annoying. Worse, if you understand an algorithm, the names or comments you write to help others will be biased by that understanding and may not help the reader as much as you think they will

He is mixing two points here:

- Stroustrup's rule - beginners want as much context as possible, experts want code to be terse and on-point

- You might be bad at explaining your ideas in code

Comments solve both problems: experts can skip them, beginners can rely on them. Bad comments are less risky than bad code - if you're bad at explaining your code in comments, people can ignore them. If you're bad at explaining your thoughts in code, everyone is stuck with it.

He casually pushes comments under the bus: "the names or comments you write to help others will be biased by that understanding and may not help the reader as much as you think they will". But his code had none so far.

This section was supposed to address the main critique from John Ousterhout: code style and design.

Then he moves to performance (Casey Muratori is not mentioned once in the book, which is a shame):

It might sound repetitive, but the trade-off comes not from cleanliness or clarity, it comes specifically from his style:

- Function extraction to keep them small (and to avoid comments)

- Moving parameters to object fields to minimize the number of parameters (to 1 or 0)

He understates the negative impact:

- Compile time: more small functions and many fields forces the compiler to do more work

- Runtime: all these object fields require additional memory space for references

- Testing: in Java, for non-JITed code, passing data via instance fields is more expensive than using method parameters. Slow non-JITed code means slow tests.

If you don't agree that this style improves clarity (and you shouldn't - be like John Ousterhout), you get a double slap: less readable code that also has worse performance. This is what makes people so energized against "clean code"™.

"Well, actually" the function that can throw an exception is not pure. A pure function must be deterministic and have no side effects. Throwing an exception is a side effect-it alters the control flow and can be observed from outside the function.

"allowing the individual methods to communicate without having to resort to passing arguments" - this is such strange wording.

Passing arguments and returning values is THE main mechanism for how functions communicate. There is no resorting here.

Tangent: Pure functions.

There is a whole section in Chapter 7: Clean Functions dedicated to Robert Martin refusing to embrace the concept of pure functions.

Purity is an observed quality, not an intrinsic quality. Therefore, whether a function is pure or not depends upon what is being observed.

Consider the C library function fopen(char* name, char* mode) This function has the side effect of leaving the named file open.

This means that fopen is not pure, because there are functions, such as fgetc and fputc, that will not behave properly unless

fopen is called first. Indeed, if you call fopen with the same arguments twice in a row without an intervening call to fclose,

the second invocation will likely fail because the file is already open. So fopen is not pure, because of the side effect that

leaves the system in an altered state.

However, we can make the fopen function appear to be pure, at least to certain observers, by ensconcing it in another function that hides the side effect.

void openAndDo(char* fileName, void (*doTo)(FILE*)) {

FILE* f = fopen(fileName, "r+");

doTo(f);

fclose(f);

}

I believe he is trying to address criticism of his misunderstanding of pure functions and side effects by doubling down on that misunderstanding.

Indeed, if you call fopen with the same arguments twice in a row without an intervening call to fclose, the second invocation will likely fail because the file is already open

On some operating systems it will fail, but on others it won’t. Instead, you may just leak file descriptors. The side effect of fopen is more complex than “leaves the file open”:

- It mutates global system state.

- It depends on external system resources being available.

- It might fail based on external conditions.

In other words, it has an implicit dependency on the environment.

at least to certain observers

For any observer:

fopencan fail,doTocan fail, andfclosecan fail. Any of these may leave the system in a different state.fopenandfcloseboth depend on the environment: the file must exist, the filesystem must be available, there must be free file descriptors, etc.

The whole point of pure functions is that they depend only on their input parameters and always produce the same result for the same input. This makes them:

- Context-independent – they can be used anywhere you have the required input data, and they compose well with other parts of the system.

- Easier to reason about – you only need to think about the function’s implementation, not hidden global or environmental state.

- Easier to optimize – they are suitable for memoization/caching and compiler optimizations

I suspect this section exists mostly to defend his “0–1 parameters” style. But again, instead of clarifying important concepts (purity and side effects), Martin blurs them just enough to justify his preferred way of writing code.

This reframing of purity as an “observed quality” in a programming book in 2025 looks off.

In isolation this is an A-OK caveat. It makes the book feel less dogmatic and given how controversial it is - that's a good tone shift. But the question is: who is Robert Martin speaking to? Junior people would just ignore this paragraph, they are looking for straight and simple guidance. Putting disclaimers like this doesn't negate the harmful influence. For senior people who are just upset with "clean code"(tm) style this is an empty platitude. Everyone who disagrees with "clean code"(tm) style knows that they are allowed to disagree. That's not the point of the criticism.

I fed my "clean" version of the above code into Grok3 and asked it to make improvements. After a bit of thought, it returned the following code, which compiled and which passed all my tests.

package fromRoman;

import java.util.Map;

public class FromRoman {

private String roman;

private static final String REGEX =

"^M{0,3}(CM|CD|D?C{0,3})(XC|XL|L?X{0,3})(IX|IV|V?I{0,3})$";

private static final Map<Character, Integer> VALUES = Map.of(

'I', 1,

'V', 5,

'X', 10,

'L', 50,

'C', 100,

'D', 500,

'M', 1000

);

/** Constructs a FromRoman instance,

validating the input Roman numeral. */

public FromRoman(String roman) {

if (!roman.matches(REGEX)) {

throw new InvalidRomanNumeralException(roman);

}

this.roman = roman;

}

/** Converts the Roman numeral to an integer. */

public int toInt() {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < roman.length(); i++) {

int currentValue = VALUES.get(roman.charAt(i));

if (i < roman.length() - 1) {

int nextValue = VALUES.get(roman.charAt(i + 1));

if (currentValue < nextValue) {

sum -= currentValue;

} else {

sum += currentValue;

}

} else {

sum += currentValue;

}

}

return sum;

}

/** Static method to convert a Roman numeral string to an integer. */

public static int convert(String roman) {

return new FromRoman(roman).toInt();

}

public static

class InvalidRomanNumeralException extends RuntimeException {

public InvalidRomanNumeralException(String roman) {

super("Invalid Roman numeral: " + roman);

}

}

}

Grok3 did a nice job

This is such a canonical solution to the Roman numeral problem that Grok almost certainly got it from the training data.

But what's interesting here is how you can bias an AI model to write suboptimal code.

Notice that Grok's solution retains the instance variable roman which is completely unnecessary.

It is a bias from his "clean" version.

If you just ask a model to create a brand new converter from "roman numerals to int in java" it would come up with a reasonable API:

public final class RomanNumerals {

public static int toInt(String roman) {...}

}

Chapter 3: First principles

Chapter 3 is supposed to demonstrate how SOLID gives you designs that scale with new requirements. What it actually demonstrates is how you can get a complex code design that completely ignores the complexity of the domain.

The starting point is a simple rental statement for a conference center.

---Statement.java---

package ubConferenceCenter;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class Statement {

public enum CatalogItem {SMALL_ROOM, LARGE_ROOM,

PROJECTOR, COFFEE, COOKIES}

public record RentalItem(CatalogItem type,

int days,

int unitPrice,

int price,

int tax) {

}

public record Totals(int subtotal, int tax) {

}

private String customerName;

private int subtotal = 0;

private int tax = 0;

private List<RentalItem> items = new ArrayList<>();

public Statement(String customerName) {

this.customerName = customerName;

}

public void rent(CatalogItem item, int days) {

int unitPrice = switch (item) {

case SMALL_ROOM -> 100;

case LARGE_ROOM -> 150;

case PROJECTOR -> 50;

case COFFEE -> 10;

case COOKIES -> 15;

};

boolean eligibleForDiscount = switch (item) {

case SMALL_ROOM, LARGE_ROOM -> days == 5;

case PROJECTOR, COFFEE, COOKIES-> false;

};

int price = unitPrice * days;

if (eligibleForDiscount) price = (int) Math.round(price * .9);

subtotal += price;

int thisTax = switch (item) {

case SMALL_ROOM, LARGE_ROOM, PROJECTOR ->

(int) Math.round(price * .05);

case COFFEE,COOKIES -> 0;

};

tax += thisTax;

items.add(new RentalItem(item, days, unitPrice, price, thisTax));

}

public RentalItem[] getItems() {

List<RentalItem> items = new ArrayList<>(this.items);

boolean largeRoomFiveDays = items.stream().anyMatch(

item -> item.type() == CatalogItem.LARGE_ROOM && item.days() == 5);

boolean coffeeFiveDays = items.stream().anyMatch(

item -> item.type() == CatalogItem.COFFEE && item.days() == 5);

if (largeRoomFiveDays && coffeeFiveDays)

items.add(new RentalItem(CatalogItem.COOKIES, 5, 0, 0, 0));

return items.toArray(new RentalItem[0]);

}

public String getCustomerName() {

return customerName;

}

public Totals getTotals() {

return new Totals(subtotal, tax);

}

}

To address the requirements changes:

The proposed rewrite is as follows:

Applying different letters from SOLID, Martin claims that SOLID helps design code for growth and scaling:

I can agree with extraction of Bonus subsystem. But why stop at Bonuses? What about taxes and discounts and pricing?

(side note: void checkAndAdd(List<RentalItem> items, List<RentalItem> bonusItems) is surprisingly awkward API)

The whole redesign is mostly an attempt to replace switch statements with polymorphism. But is CatalogItem actually a good interface?

public interface CatalogItem {

boolean isEligibleForDiscount(int days);

int getDiscountedPrice(int days);

int getUnitPrice();

double getTaxRate();

String getName();

}

This is old-school OOP: one interface that pretends to encapsulate “an item” but quietly bundles pricing, tax, and discount policy into a single interface.

And yet it is very simplistic.

Everyone who has dealt with taxes can immediately understand how laughable this simplification is:

double getTaxRate();

- There's rarely just one tax

- Taxes depend on the category of item

- Tax depends on where and who

- Tax rules change over time

- double wouldn't cut it for rounding and precision, some taxes are not even percentages.

The requirement changes that this design wouldn't be able to accommodate:

- Actual taxation system

- Changes over time

For example, Martin's interface makes a fundamental domain modeling error: it treats tax as an intrinsic property of items.

Say we're expanding state tax rules: New York charges 8.875% on room rentals but 0% on food. California charges 7.25% on both. With Martin's design, where does this logic go?

class LargeRoom implements CatalogItem {

double getTaxRate() {

// How do I know we're in NY vs CA?

// Do I inject location into every item?

}

}

I don't believe this design is ready for "new markets, new states, new laws to contend with."

This is one of the problems with SOLID in general: it's a collection of principles that you can apply mechanistically to any codebase, completely ignoring the domain of the application.

This idea of separating high-level policy from low-level detail might be useful, but it is misapplied. The real world of taxation doesn't work by each newly produced item (low-level) deciding its own tax rate. And yes, tax code (high level) has to change to accommodate new categories when they are being introduced.

This is where domain-driven design provides better guidance: instead of mechanically applying structural principles, start by understanding what you're building.

- Figure out the goal of the application

- Figure out main domain areas

- Figure out main domain entities

- Figure out processing workflows

It is easier to organize growing space, by abandoning old OOP-style of mixing data and processing in one interface.

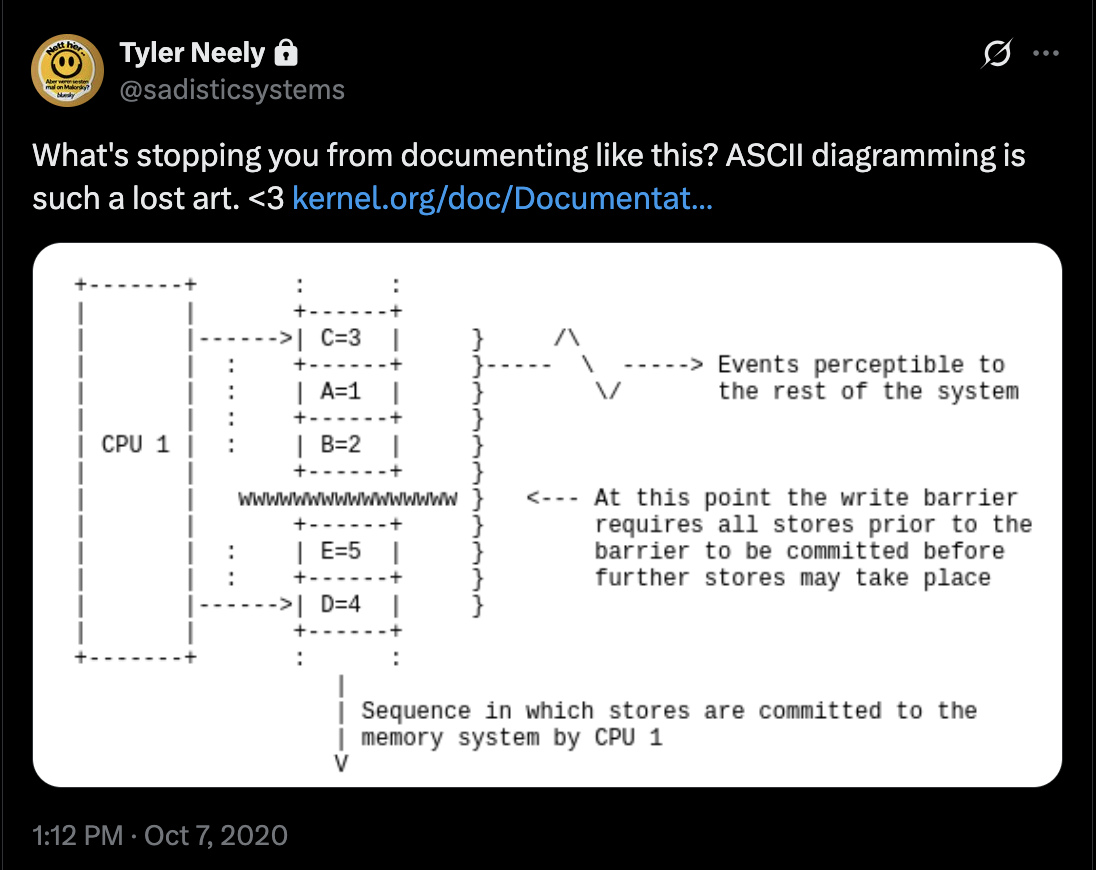

For this rental system, the processing flow is straightforward:

[order] -> <discounts> -> <promotions> -> <pricing> -> <taxation> -> [receipt]

And the sketch would look like this:

// data

record RoomRental(RoomType type, int days) {}

record EquipmentRental(EquipmentType type, int days) {}

record ConsumableOrder(ConsumableType type, int days) {}

class Order {

private List<RoomRental> rooms = new ArrayList<>();

private List<EquipmentRental> equipment = new ArrayList<>();

private List<ConsumableOrder> consumables = new ArrayList<>();

}

record BillingDetails(

String customerName,

String billingAddress,

String taxId,

PaymentMethod paymentMethod

) {}

// processing

var pricing = new PricingEngine(discounts, taxes, promotions);

var order = new Order()

.addRoom(Rooms.LARGE, 5)

.addRoom(Rooms.SMALL, 3)

.addEquipment(Equipment.PROJECTOR, 3)

.addConsumable(Consumables.COFFEE, 5);

var billingDetails = new BillingDetails(

"Acme Corp",

"123 Business St, New York, NY 10001",

"EIN: 12-3456789",

PaymentMethod.CORPORATE_ACCOUNT

);

Receipt receipt = pricing.generateReceipt(order, billingDetails);

This is a sketch, but it clearly has space for growth into a real system: Need to add California tax rules? Add a new tax strategy. New promotion for repeat customers? Add it to the promotions engine. Etc

Applying SOLID without thinking about domain modeling, will produce architecturally wrong designs that won't work.

Chapter 5: Comments

In the revised chapter on comments, he refuses to take the blame for popularizing the idea that comments are a sign of bad code and should be avoided:

And yet even in this edition he declares comments to be a failure:

..

The proper use of comments is to compensate for our failure to express ourselves in code. Note that I used the word failure. I meant it. Comments are always failures of either our languages or our abilities.

I would generalize even more: this is a failure of our universe. If only the laws of our universe were better, we could avoid writing comments.

Both editions of this book are seriously lacking examples of good comments. The chapter about comments has a section "Good comments" and all examples are comically bad.

One of the more common motivations for writing comments is bad code. We write a module and we know it is confusing and disorganized. We know it's a mess. So we say to ourselves, "Ooh, I'd better comment that!" No! You'd better clean it!

Expressing thoughts in code is harder than expressing thoughts in plain text. Expressing thoughts in code requires:

- Clear thinking

- Mastery of the language

- Expressiveness of the language

For example, you can try very hard, but the expressiveness of the language is a noticeable limiting factor:

assertTrue(b.compareTo(a) == 1); // b < a

The best Java can offer is:

assertThat(a).isGreaterThan(b);

Serious note: if you have messy code, sit down and try to write clear comments - it will clarify your thinking and might help you reorganize the original mess.

Or another example from Chapter 7: Clean functions:

if(employee.shouldBePaidToday())

employee.pay();

In this example the employee class/interface is now coupled with unrelated concerns:

- calendars

- schedules

- payment transactions

Does this read like prose? Maybe. Is it a good interface design? No, it isn't. Some languages are just not expressive enough for you to satisfy both constraints: good code design and "reading like prose".

Overall the messaging of this chapter is the same. It's overfocused on bad examples and underfocused on good ones.

// Returns an instance of the Responder being tested.

protected abstract Responder responderInstance();

That's because the author was using the well-known Singleton design pattern. When you use a design pattern like that, you should follow the canonical form specified by that pattern. In the Singleton pattern, the name of the accessor function always ends in the word Instance.

This doesn't look like a singleton. At all.

This is how a typical singleton should look (in Java):

class Responder {

public static final Responder INSTANCE = createResponder();

}

I don't know what has happened here. But assuming that the suffix Instance means singleton is just wrong.

I've checked the source code of Fitnesse.

And I'm sorry to inform you this is not a singleton.

A couple of notes that irritate me:

/* Added by Rick */

This is just graffiti. Please don't spray-paint your name all over the source code. Source code control systems are very good at remembering who added what, when.

I'm surprised to hear this argument from an IT veteran who for sure should have seen mass migration from one version control system to another (CVS to SVN or from SVN to Git). And how often the authorship information is lost during such migrations.

Few practices are as odious as commenting-out code. Commented-out code is an abomination before nature and nature's God. Don't check this stuff in!

Others who see that commented-out code will be unlikely to have the courage to delete it. They'll think it is there for a reason and is too important to delete. So commented-out code gathers like dregs at the bottom of a bad bottle of wine

In reality, nobody is afraid to delete old commented-out code; once it’s been sitting there for a year or two, everyone assumes it’s stale. And for short-lived changes, commenting code in and out is far more practical and convenient than anything else.

I don't know where this puritan stance against comments is coming from. Comments can be fun, creative and useful:

Feel free to use and enjoy them.

...

And one last thing..

Exception handling is still a mess, even two decades later:

public void loadProperties()

{

try

{

String propertiesPath = propertiesLocation + "/" + PROPERTIES_FILE;

FileInputStream propertiesStream =

new FileInputStream(propertiesPath);

loadedProperties.load(propertiesStream);

}

catch(IOException e)

{

// No properties files means all defaults are loaded

}

}

... Wouldn't it have been better if the programmer had written the following?

catch(IOException e)

{

LoadedProperties.loadDefaults();

}

No! It wouldn't. This is very sloppy code for several reasons:

-

IOException is too broad: This exception type can occur for many reasons-file not found, permission denied, disk full, corrupted data, network issues (for network filesystems), and more.

-

Silent failures make debugging impossible: When this code fails in production, you'll have no idea why the defaults were loaded. That information is gone.

-

The fallback might not be safe: Loading defaults might be the right response to "file not found" but completely wrong for "disk full" or "permission denied." Different IOException causes should trigger different recovery strategies.

The correct approach would be something like:

catch(FileNotFoundException e) {

logger.info("Config file not found, the execution would proceed using defaults", e);

LoadedProperties.loadDefaults();

} catch(IOException e) {

throw new ConfigurationException("Unable to load configuration", e);

}

If you think that I'm nit-picking, I promise you that I'm not. Proper handling of error cases is one of the main pillars of software engineering. Just another illustration that Clean Code (the book) is obsessed with style aesthetics and underweights operational reality.

Small functions are a style, but good error handling is clean code.

Reference Materials

If you want to learn more about domain-driven design and domain modeling, here are some excellent resources:

- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by Eric Evans - The foundational book that introduced DDD concepts

- Implementing Domain-Driven Design by Vaughn Vernon - Practical guide to applying DDD in real projects

- Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin - Shows how to use functional programming with DDD (uses F#)

- Functional and Reactive Domain Modeling by Debasish Ghosh - Combines DDD with functional programming

For performance critique of Clean Code style:

- "Clean" Code, Horrible Performance by Casey Muratori - Demonstrates the performance cost of Clean Code patterns

Clean Code - Critical Analysis

Clean code is probably the most recommended book to entry level engineers and junior developers. While it might have been good recommendation in the past, I don't believe that's the case anymore.

After revisiting the book in 2023 I was surprised to notice that:

- The book hasn't aged well

- Much of its advice ranges from questionable to harmful

- Examples are the worst part of the book. By any objective metrics, many would qualify as "bad code."

- Lazer focus on a wrong thing and attempt to sell it as the solution to everything. Code readability is important, it is not the only one aspect

- Despite being an entry-level book, it has these vibes of implied superiority, potentially giving the readers an undeserved sense of expertise

For a significantly shorter critque of the book, check out qntm's critique. I mostly agree with qntm assessment. But it's a bit too emotional and personal and doesn't cover the parts i find the most harmful.

Recommended Alternatives

If you're just starting your career and seeking books to improve your coding skills, I suggest these instead:

-

A Philosophy of Software Design

While not explicitly positioned as such, this book effectively counters many "Clean Code" principles. It's particularly helpful for unlearning Clean Code style of coding. -

The Art of Software Design: Balancing Flexibility and Coupling A deep dive into software complexity through abstraction, coupling, and modularity. It works as an excellent companion to "A Philosophy of Software Design".

Also Robert Martin is working on the second edition of Clean Code. It will be fun to see how much of this critique will become irrelevant 😃

Intended Audience

- For those recommending "Clean Code":

You may have read the book over a decade ago and found it useful at the time. This might help you reconsider. - For those confused after reading "Clean Code":

You’re not alone. The book can be confusing, and you might find better practical advice in modern alternatives - For those who enjoyed "Clean Code":

"It's great when people get excited about things, but sometimes they get a little too excited."

I hope this critique would help you to see more nuance.

A Note to All Readers

This page exists as a reference for anyone. Agree or disagree, contributions to the critique are welcome via GitHub.

Chapter 1: Clean Code

Here is Martin's main thesis: bad code destroys companies.

Ergo: Writing bad code is a mistake, and no excuse can justify it.

Two decades later I met one of the early employees of that company and asked him what had happened. The answer confirmed my fears. They had rushed the product to market and had made a huge mess in the code. As they added more and more features, the code got worse and worse until they simply could not manage it any longer.

It was the bad code that brought the company down.

A Counter-Anecdote:

"Oracle Database 12.2.

It is close to 25 million lines of C code. What an unimaginable horror! You can't change a single line of code in the product without breaking 1000s of existing tests. Generations of programmers have worked on that code under difficult deadlines and filled the code with all kinds of crap.

Very complex pieces of logic, memory management, context switching, etc. are all held together with thousands of flags. The whole code is ridden with mysterious macros that one cannot decipher without picking a notebook and expanding relevant parts of the macros by hand. It can take a day to two days to really understand what a macro does.

Sometimes one needs to understand the values and the effects of 20 different flags to predict how the code would behave in different situations. Sometimes 100s too! I am not exaggerating."

From HN: What's the largest amount of bad code you have ever seen work?

As horrific as this sounds, Oracle won't go out business anytime soon. I can bet my life on that.

A personal anecdote:

I worked in a small Series-A startup that had the most elegant code I've ever seen. The code was highly attuned to the domain model, well-structured and was so ergonomic that adding new features was a joy. It was the third iteration of the codebase. They run out of money. It was the hunt for the clean code that brought the company down. Nah. I'm kidding. World of business is far more complex than just code quality.

Reading Clean Code in 2009, the idea that bad code being the root of all evil impressed me and I became a convert. It took me a decade to finally admit "ok. this doesn't match with reality." "Bad" code is pretty much the norm. Success or failure of an enterprise has nothing to do with it. And code that's good today will be very questionable from tomorrow's standards (this book is a perfect illustration of this).

The focus on "cleanliness" of the code often feels like bike-shedding. The real challenge is to keep the balance between complexity vs available resources to manage it. Oracle can afford to have complex code base as they have enough resources and (I'm speculating) keep throwing more bodies at the problem.

Were you trying to go fast? Were you in a rush? Probably so. Perhaps you felt that you didn't have time to do a good job

"Not having enough time" might be an easy excuse and rationalization. But in my experience, I'm writing bad code because:

- I don't know that it is bad

- I don't know how to make it good within the constraints

- The existing architecture or design

More often, it's a combination: accepting the existing design because I don't know how to make it better.

You don't know what you don't know. Unfortunately, just reading "Clean Code" helps very little with discovering unknowns.

The Boy Scout Rule

"Leave the campground cleaner than you found it". This is the call to action: always improve code that you're touching.

In corporate america anything that has a catchy name has a chance to spread. I've heard of CTO at a mid-size company who knew two things about IT: how to hire contractors to adapt Scaled Agile Framework and "the Boy Scout Rule" of programming.

This sounds appealing and might work on a small scale (think couple lines of code) and in isolation. But on this scale, it quickly hits diminishing returns. Applied on a larger scale, it creates chaos, random failures, and placing unnecessary burden on people working with the system and the codebase.

What makes things worse: cleanliness of code is not an objective metric.

In a campground, everyone agrees a plastic cup is trash and doesn’t belong. In code, readability and elegance are far more subjective. The most elegant OCaml code will be unreadable and weird in the eyes of average java Bob.

Kent Beck offers the idea of tidyings - small code changes that will unquestionably improve code base. While reading the book "Tidy first?" you'll notice two things:

- These are very small changes

- Question mark in the title of the book

Clean Code advocates for significantly more radical interventions.

The boy scout rule is the opposite of:

To Sum Up:

Focusing obsessively on clean code often misses the bigger picture. The real game lies in managing complexity while balancing the resources and the constraints.

Chapter 2: Meaningful names

I agree with the theme of this chapter: names are important. Naming is the main component of building abstractions and abstraction boundaries. In smaller languages like C or Go-Lang, naming is the primary mechanism for abstraction.

Naming brings the problem domain into the computational domain:

static int TEMPERATURE_LIMIT_F = 1000;

Named code constructs — such as functions and variables — are the building blocks of composition in virtually every programming paradigm.

Names are a form of abstraction: they provide a simplified way of thinking about a more complex underlying entity. Like other forms of abstraction, the best names are those that focus attention on what is most important about the underlying entity while omitting details that are less important.

However, I disagree with Clean Code's specific approach to naming and its examples of "good" names. Quite often the book declares a good rule but then shows horrible application.

Use intention-revealing names

The advocated principle is the title - the name should reveal intent. But the application:

This sounds like an impossible task to me. First, the name that reveals all of those details fails to be an abstraction boundary. Second, what you notice in many examples in the book this approach leads to using "description as a name".

Martin presents 3 versions of the same code:

public List<int[]> getThem() {

List<int[]> list1

= new ArrayList<int[]>();

for (int[] x : theList)

if (x[0] == 4)

list1.add(x);

return list1;

}

public List<int[]> getFlaggedCells() {

List<int[]> flaggedCells

= new ArrayList<int[]>();

for (int[] cell : gameBoard)

if (cell[STATUS_VALUE] == FLAGGED)

flaggedCells.add(cell);

return flaggedCells;

}

public List<Cell> getFlaggedCells() {

List<Cell&ht; flaggedCells

= new ArrayList<Cell>();

for (Cell cell : gameBoard)

if (cell.isFlagged())

flaggedCells.add(cell);

return flaggedCells;

}

My main disagreement is this: not all code chunks need a name. In modern languages, this method can be a one-liner:

gameBoard.filter(cell => cell(STATUS_VALUE) == FLAGGED)

That's it. This code can be inlined and used as is.

While getFlaggedCells looks like an improvement over obfuscated getThem, it's not a name, it's a description.

If the description is as long as the code, it is redundant.

Martin writes about it in passing: "if you can extract another function from it with a name that is not merely a restatement of its implementation".

But he violates this principle quite often.

For readability, the second version is just as clear as the third. Adding a Cell abstraction is overkill.

List<int[]> is a generic type - devoid of meaning without a context. List<Cell> - has more semantic meaning and is harder to misuse.

List<int[]> list = getFlaggedCells();

list.get(0)[0] = list.get(0)[1] - list.get(0)[0];

List<Cell> has a better affordance than List<int[]>, and makes such mistakes less likely. But improved affordance comes from the specialized type, not just the name.But there is a the downside - specialized types needs specialized processing code. Serialization libraries, for example, would have support for

List<int[]> out of the box,

but would need custom ser-de for the Cell class.Since Clean Code, Robert Martin has embraced Clojure and functional programming. One of the tenets of Clojure philosophy: use generic types to represent the data and you'll have enormous library of processing functions that can be reused and combined.

I'm curious if he would ever finish the second edition and if he had changed his mind about types.

Avoid disinformation ... Use Problem Domain Name

Martin pretty much advocates for informative style of writing in code: be clear, avoid quirks and puns.

These are examples of "good" names from his perspective:

bunchOfAccountsXYZControllerForEfficientStorageOfStrings

This might be stylistic preferences, but accountsList is easier to read and write than bunchOfAccounts: it's shorter and has fewer words - it is more concise. If by looking at word List the first thing you're thinking is java.util.List, then you might need some time away from Java. Touch some grass, write some Haskell.

Martin states that acronyms and word shortenings are bad, but doesn't see the problem in a name that has 7 words and 40 characters in it.

There is a simple solution to this - comments that expand acronyms and explain shortenings. But because Martin believes that comments are a failure, he has to insist on using essays as a name.

By the end of the chapter he finally mentions:

...The resulting names are more precise, which is the point of all naming.

These are really good points! But most of the examples in the chapter are not aligned with them. And I don't think "short and concise naming" is a takeaway people are getting from reading this chapter.

If anything, in most examples he proposed to replace short (albeit cryptic) names with 3-4 word long slugs.

The idea being that

ItIsReallyUncomfortableToReadLongSentencesWrittenInThisStyle. Hence people will be soft forced to limit the size of names.The assumption was wrong.

Add meaningful context

I believe this was my first big WTF moment in the book:

private void printGuessStatistics(char candidate,

int count) {

String number;

String verb;

String pluralModifier;

if (count == 0) {

number = "no";

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

} else if (count == 1) {

number = "1";

verb = "is";

pluralModifier = "";

} else {

number = Integer.toString(count);

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

}

String guessMessage = String.format(

"There %s %s %s%s", verb, number,

candidate, pluralModifier

);

►print(guessMessage);Instead of printing, the method should just return guessMessage String result

}public class GuessStatisticsMessage {

private String number;

private String verb;

private String pluralModifier;

public String make(char candidate, int count) {

createPluralDependentMessageParts(count);

return String.format(

"There %s %s %s%s",

verb, number, candidate, pluralModifier );

}

private void createPluralDependentMessageParts(int count) {

if (count == 0) {

thereAreNoLetters();

} else if (count == 1) {

thereIsOneLetter();

} else {

thereAreManyLetters(count);

}

}

private void thereAreManyLetters(int count) {

number = Integer.toString(count);

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

}

private void thereIsOneLetter() {

number = "1";

verb = "is";

pluralModifier = "";

}

private void thereAreNoLetters() {

number = "no";

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

}

}In no way the second option is better than the first one. The original has only one problem: side-effects. Instead of printing to the console it should have just return String.

And that is it:

- 1 method, 20 lines of code, can be read top to bottom,

- 3 mutable local variables to capture local mutable state that can not escape.

- It is thread-safe. I's impossible to misuse this API.

Second option:

- 5 methods, 40 lines of code, +1 new class with mutable state.

- Because it's a class, the state can escape and be observed from the outside.

- Which makes it not thread safe.

The second option introduced more code, more concepts and more entities, introduced thread safety concerns.. while getting the exactly same results.

It also violates one of the rules laid out in the chapter about method names: "Methods should have verb or verb phrase names". thereIsOneLetter() is not really a verb or a verb phrase.

If I'll try to be charitable here: Martin is creating internal Domain Specific Language(DSL) for a problem.

For example, new GuessStatisticsMessage().thereAreNoLetters() looks weird and doesn't make sense.

On the other hand, language consturcts are presented in a somewhat declarative style:

private void thereAreNoLetters() {

number = "no";

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

}

private void thereIsOneLetter() {

number = "1";

verb = "is";

pluralModifier = "";

}

I hope you agree that methods like this is not a typical Java. If anything, this looks closer to typical ruby.

But ultimately, object-oriented programming and domain-specific languages are unnessary for the simple task. In a powerful-enough language, keeping this code procedural gives the result that is short and easy to understand:

def formatGuessStatistics(candidate: Char, count: Int): String = {

count match {

case i if i < 0 => throw new IllegalArgumentException(s"count=$count: negative counts are not supported")

case 0 => s"There are no ${candidate}s"

case 1 => s"There is 1 ${candidate}"

case x => s"There are $x ${candidate}s"

}

}

Chapter 3: Functions

The chapter begins by showcasing an example of "bad" code:

public static String testableHtml(PageData pageData, boolean includeSuiteSetup) throws Exception {

WikiPage wikiPage = pageData.getWikiPage();

StringBuffer buffer = new StringBuffer();

if (pageData.hasAttribute("Test")) {

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

WikiPage suiteSetup =

PageCrawlerImpl.getInheritedPage(

SuiteResponder.SUITE_SETUP_NAME, wikiPage

);

if (suiteSetup != null) {

WikiPagePath pagePath = suiteSetup.getPageCrawler().getFullPath(suiteSetup);

String pagePathName = PathParser.render(pagePath);

buffer.append("!include -setup .")

.append(pagePathName)

.append("\n");

}

}

WikiPage setup =

PageCrawlerImpl.getInheritedPage("SetUp", wikiPage);

if (setup != null) {

WikiPagePath setupPath = wikiPage.getPageCrawler().getFullPath(setup);

String setupPathName = PathParser.render(setupPath);

buffer.append("!include -setup .")

.append(setupPathName)

.append("\n");

}

}

buffer.append(pageData.getContent());

if (pageData.hasAttribute("Test")) {

WikiPage teardown = PageCrawlerImpl.getInheritedPage("TearDown", wikiPage);

if (teardown != null) {

WikiPagePath tearDownPath = wikiPage.getPageCrawler().getFullPath(teardown);

String tearDownPathName = PathParser.render(tearDownPath);

buffer.append("\n")

.append("!include -teardown .")

.append(tearDownPathName)

.append("\n");

}

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

WikiPage suiteTeardown =

PageCrawlerImpl.getInheritedPage(

SuiteResponder.SUITE_TEARDOWN_NAME,

wikiPage

);

if (suiteTeardown != null) {

WikiPagePath pagePath = suiteTeardown.getPageCrawler().getFullPath (suiteTeardown);

String pagePathName = PathParser.render(pagePath);

buffer.append("!include -teardown .")

.append(pagePathName)

.append("\n");

}

}

}

pageData.setContent(buffer.toString());

return pageData.getHtml();

}

And the proposes refactoring:

public static String renderPageWithSetupsAndTeardowns(PageData pageData, boolean isSuite) throws Exception {

boolean isTestPage = pageData.hasAttribute("Test");

if (isTestPage) {

WikiPage testPage = pageData.getWikiPage();

StringBuffer newPageContent = new StringBuffer();

includeSetupPages(testPage, newPageContent, isSuite);

newPageContent.append(pageData.getContent());

includeTeardownPages(testPage, newPageContent, isSuite);

pageData.setContent(newPageContent.toString());

}

return pageData.getHtml();

}

The original version operates on multiple levels of detalization and juggles multiple domains at the same time:

- API for fitness objects: working with

WikiPage,PageData,PageCrawleretc - Java string manipulation: Using StringBuffer to optimize string concatenation (it should be StringBuilder).

- Business logic: Handling suites, tests, setups, and teardowns in a specific order.

When everything presented at the same level it indeed looks very noisy and hard to follow. (the book touches this in "One Level of Abstraction per Function")

Martin's trick here is simple: show that smaller code is easier to understand than larger code.

This works because he doesn't show the implementation of includeSetupPages and includeTeardownPages

But... extracting non-reusable methods doesn’t actually reduce complexity or code size, at best it just improves navigation.

What objectively reduces code size is removing repetitions (the fancy term - Anti-Unification): the original code as bad as it is can be significantly improved by a small change - extract code duplication into helper method:

public static String testableHtml(PageData pageData, boolean includeSuiteSetup) {

if (pageData.hasAttribute("Test")) { // not a test data page

return pageData.getHtml();

}

WikiPage wikiPage = pageData.getWikiPage();

List<String> buffer = new ArrayList<>();

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

buffer.add(generateInclude(wikiPage, "Suite SetUp", "-setup"));

}

buffer.add(generateInclude(wikiPage, "SetUp", "-setup"));

buffer.append(pageData.getContent());

buffer.add(generateInclude(wikiPage, "TearDown", "-teardown"));

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

buffer.add(generateInclude(wikiPage, "Suite TearDown", "-teardown"))

}

pageData.setContent(buffer.stream().filter(String::nonEmpty).join("\n"));

return pageData.getHtml();

}

private static String generateInclude(WikiPage wikiPage, String path, String command) {

WikiPage inheritedPage = PageCrawlerImpl.getInheritedPage(path, wikiPage);

if (inheritedPage != null) {

WikiPagePath pagePath = inheritedPage.getPageCrawler().getFullPath(inheritedPage);

String pagePathName = PathParser.render(pagePath);

return "!include " + command + " ." + pagePathName;

} else {

return "";

}

}

Is it noisier than Martin's version? Yes. But most people would answer "YES" to the posed question "Do you understand the function after three minutes of study?" And it's a small change to the original mess.

The real problem

Despite these improvements, we're missing the critical issue: both versions modify the PageData object as a side effect.

Both testableHtml and renderPageWithSetupsAndTeardowns overwrite PageData's content to generate HTML.

This hidden behavior, not the code structure, is the real problem.

Small!

NO!

This is one of the two most harmful ideas in Clean Code.

Bazzilion small functions has become a trademark of "clean-coders" and it fundamental misunderstanding why we break down code.

(the second worst idea of the book is that "Comments are a failures").

Breaking a system into pieces is an extremely useful technique for:

- Building reusable components

- Keeping unrelated concerns separate

- Reducing cognitive load required to reason about components independently

However clean code advocates for splitting the code in order to just keep functions short. By itself this is a useless metric.

When components become too small, they:

- Fail to encapsulate meaningful functionality

- Become tightly coupled with other parts

- Can't be analyzed independently

This defeats the original goals of modularity:

- Less reusable: Tight coupling makes it harder to use pieces of the system in different contexts.

- Harder to understand: You can't reason about pieces in isolation—everything is interconnected

You can argue that shorter methods are less complex, but this addresses only local complexity. To understand a system, you have to deal with global complexity - the sum of all the pieces and how they interact. A bad split can make global complexity worse.

Most of the time, splitting a function into tiny pieces doesn’t improve much. This is like cutting a pizza into smaller slices and claiming you've reduced the calories.

My rule of thumb: splitting code should reduce global complexity or code size (preferrably both). If breaking something into smaller pieces makes the overall system harder to understand and/or adds more lines of code, you’ve just made things worse.

There’s also the problem of running out of good names when you create too many small functions. This leads to long, over-descriptive names that actually make code harder to read (more on this later):

// an example, not from the book

public static String render(PageData pageData, boolean isSuite) throws Exception

private static String renderPageWithSetupsAndTeardowns(PageData pageData, boolean isSuite) throws Exception

private static String failSafeRenderPageWithSetupsAndTeardowns(PageData pageData, boolean isSuite) throws Exception

PS Unfortunately, Martin still advocates for this approach:

How Small Should a Function be? By Uncle Bob pic.twitter.com/hhk61RpXSp

— Mohit Mishra (@chessMan786) December 14, 2024

One Level of Abstraction per Function

This is a good rule, but as an author of the code you have always a choice: what is your abstraction.

public static String testableHtml(PageData pageData, boolean includeSuiteSetup) {

WikiPage wikiPage = pageData.getWikiPage();

StringBuilder buffer = new StringBuilder();

boolean isTestPage = pageData.hasAttribute("Test");

if (isTestPage) {

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

buffer.append(generateInclude(wikiPage, SuiteResponder.SUITE_SETUP_NAME, "-setup")).append("\n")

}

buffer.append(generateInclude(wikiPage, "SetUp", "-setup")).append("\n")

}

buffer.append(pageData.getContent());

if (isTestPage) {

buffer.append(generateInclude(wikiPage, "TearDown", "-teardown"))

if (includeSuiteSetup) {

buffer.append("\n").append(generateInclude(wikiPage, SuiteResponder.SUITE_TEARDOWN_NAME, "-teardown"))

}

}

pageData.setContent(buffer.toString());

return pageData.getHtml();

}

You might say this violates "one level of abstraction":

others that are at an intermediate level of abstraction, such as: String pagePathName = PathParser.render(pagePath);

and still others that are remarkably low level, such as: .append("\n").

Or.. you could also argue that the domain of this function is to convert PageData into HTML as a raw string. From that perspective, everything here operates at the same level - transforming structured data into formatted text.

James Koppel "Abstraction is not what you think it is"

The key point is that abstraction is a choice. Developers define the idealized world their function operates in. If you decide your abstraction is "PageData to HTML converter," then string operations and HTML generation belong at the same level.

Switch Statements

By this logic a method can never have if-else statement - they also do N things.

There was a whole movement of anti-if programming. I'm not quite sure if it's a joke or not

Ok, back to Martin:

public Money calculatePay(Employee e) throws InvalidEmployeeType {

switch (e.type) {

case COMMISSIONED:

return calculateCommissionedPay(e);

case HOURLY:

return calculateHourlyPay(e);

case SALARIED:

return calculateSalariedPay(e);

default:

throw new InvalidEmployeeType(e.type);

}

}

Whether this violates the "one thing" rule depends entirely on perspective:

- Low-level view: Four branches doing four different things

- High-level view: One thing - calculating employee pay

Switch statements have bad rep among Java developers:

- Doesn't look like OOP

- Leads to repetition

- Lead to bugs when copies get out of sync

Starting from Java 13 switch expressions introduced exhaustive matching, addressing one of these issues.

public Money calculatePay(Employee e) throws InvalidEmployeeType {

return switch (e.type) {

case COMMISSIONED -> yield calculateCommissionedPay(e);

case HOURLY -> yield calculateHourlyPay(e);

case SALARIED -> yield calculateSalariedPay(e);

}

}

Forgetting to handle a case now causes compile-time errors that's improssible to miss. No extra abstractions needed.

Martin suggests hiding the switch statement behind polymorphism:

public abstract class Employee {

public abstract boolean isPayday();

public abstract Money calculatePay();

public abstract void deliverPay(Money pay);

}

public interface EmployeeFactory {

public Employee makeEmployee(EmployeeRecord r) throws InvalidEmployeeType;

}

public class EmployeeFactoryImpl implements EmployeeFactory {

public Employee makeEmployee(EmployeeRecord r) throws InvalidEmployeeType {

switch (r.type) {

case COMMISSIONED:

return new CommissionedEmployee(r);

case HOURLY:

return new HourlyEmployee(r);

case SALARIED:

return new SalariedEmploye(r);

default:

throw new InvalidEmployeeType(r.type);

}

}

}

This common approach has serious problems, as Martin's own example shows.

His Employee interface becomes a god object mixing unrelated concerns:

Employee.isPayday()- couples Employee with payments, agreements, calendars and datesEmployee.calculatePay()- couples Employee with financial calculationsEmployee.deliverPay()- couples Employee with transaction processing and persistence

As more features will be added, the Employee interface will inevitably grow into an unmanageable, bloated entity

Ironically, Chapter 10 talks about cohesion and single responsibility principle. Yet here, to avoid a switch, he violates these core OOP principles.

By declaring switch fundamentally bad, Martin loses this balance. His solution increases complexity and couples unrelated concerns, trading one set of problems for another.

To properly separate concerns, we'd need to split Employee into focused interfaces like Payable, Schedulable, and Transactionable.

But to maintain polymorphism, we'd then need either three factories (repetition) or a factory of factories (over-engineering).

Use Descriptive Names

Nit-picking but SetupTeardownIncluder.render doesn't make much sense without reading the code. It's unclear why "Includer" should be rendering, and what does "rendering" mean for the "includer".

Using descriptive names is good. Using descriptions as names isn't.

I think you should. Between using cryptic acronyms and writing "essay as a name" there is a balance to be found.

There's scientific evidence that long words or word combinations increase both physical and mental effort when reading:

"When we read, our eyes incessantly make rapid mechanical (i.e., not controlled by consciousness) movements, saccades. On average, their length is 7-9 letter spaces. At this time we do not receive new information."

"During fixation, we get information from the perceptual span. The size of this area is relatively small, in the case of alphabetic orthographies (for example, in European languages) it starts from the beginning of the fixed word, but no more than 3-4 letter spaces to the left of the fixation point, and extends to about 14-15 letter spaces to the right of this point (in total 17-19 spaces)."

Figure 10. The typical pattern of eye movements while reading.

From: Optimal Code Style

Names longer than ~15 characters become harder to process. Compare:

-

PersistentItemRecordConfig -

PersistentItemRec

If you’re not thinking about the meaning, the second name is visually and mentally easier to skim. The first name requires more effort to read and pronounce internally.

Long names also consume real estate of the screen and make code visually overwhelmiing.

PersistentItemRecordConfig persistentItemRecordConfig = new PersistentItemRecordConfig();

vs

val item = new PersistentItemRec()

Consider Bob Nystrom’s principles of good naming as a guide:

A name has two goals:

- It needs to be clear: you need to know what the name refers to.

- It needs to be precise: you need to know what it does not refer to.

After a name has accomplished those goals, any additional characters are dead weight

- Omit words that are obvious given a variable’s or parameter’s type

- Omit words that don’t disambiguate the name

- Omit words that are known from the surrounding context

- Omit words that don’t mean much of anything

From Long Names Are Long

A Note on Experience Levels

I've recently read about "Stroustrup's Rule". The short version sounds like: "Beginners need explicit syntax, experts want terse syntax."

I see this as a special case of mental model development: when a feature is new to you, you don't have an internal mental model so need all of the explicit information you can get. Once you're familiar with it, explicit syntax is visual clutter and hinders how quickly you can parse out information.

(One example I like: which is more explicit, user_id or user_identifier? Which do experienced programmers prefer?)

That is a good insight.

And yet it is more appropriate to put the information required for "begginers" (those who are unfamiliar with a code base) into comments.

This way "experts" don't need to suffer from visual clutter.

Function Arguments

Next comes one (monadic), followed closely by two (dyadic).

Three arguments (triadic) should be avoided where possible.

More than three (polyadic) requires very special justification—and then shouldn't be used anyway.

I think Robert Martin gets the most amount of hate for this one.

The main problem with Martin's advice: it presents itself as "less is better" but handwaves all the downsides of the particular application. He ignores trade-offs and side effects.

- "Smaller methods are better", but the increased amount of methods? Nah, you'll be fine.

- "Less arguments for a function is better", but the increased scope of mutable state? Nah, you'll be fine

- "Compression is better", but the bulging discs? Nah, you'll be fine.

One particularly odd suggestion is to "simplify" by moving arguments into instance state:

StringBuffer in the example. We could have passed it around as an argument rather than making it an instance variable,

but then our readers would have had to interpret it each time they saw it.

When you are reading the story told by the module, includeSetupPage() is easier to understand than includeSetupPageInto(newPageContent)

This doesn't eliminate complexity - it relocates it. But worse: moving parameters to fields increases size and the scope of the mutable state of the application. This sacrifices global complexity to reduce local one. Tracking shared mutable state in multi-threaded environments is far harder than understanding function arguments.

But this just shifts the burden. Method calls become simpler, but setting up test instances and tracking state becomes harder. Not a winning trade.

Ironically, functional programming exists specifically to limit mutable state, recognizing its cognitive cost. Martin clearly wasn't a fan at the time of writing Clean Code.

Beating the same dead horse: render(pageData) might be easy to understand. SetupTeardownIncluder.render(pageData) still doesn't make sense.

Flag Arguments

Martin’s critique of flag arguments is front-loaded with emotion, but is it valid?

Adding boolean or any parameter is indeed a complication. Since boolean can accept 2 states, speaking more formaly adding boolean is doubling the domain space of the function.

Adding a boolean parameter to a function that already has 2 booleans will bring domain space from 4 to 8, this might be significant. But adding boolean argument to a function that had none before would not kick complexity level into "unmanagable" territorry. It might be a tolerable increase.

While render(true) is indeed unclear on a caller side, modern programming languages offer solutions, such as named parameters:

render(asSuite = true) # costs nothing in runtime

The deeper problem with render(true) is so-called boolean blindness

from Boolean Blindness

A better solution: Use enums to preserve semantic meaning:

enum ExcutionUnit {

SingleTest,

Suite

}

//...

public String renderAs(ExecutionUnit executionUnit) { ... }

// ------

//calling side:

renderAs(ExeuctionUnit.Suite);

It's unclear if Robert Martin likes enums.

The inherit unavoidable complexity is that tests can have 2 execution types: as a single test or as a part of a suite.

Splitting the render function "into two: renderForSuite() and renderForSingleTest()" does not reduce it. (neither does using boolean or enum)

It is still 2 types of execution.

There will be place in code that would have to take a decision and select one of the branches.

Please do not create Abstract Factory for every boolean in your code.

Verbs and Keywords

For example, assertEquals might be better written as

assertExpectedEqualsActual(expected, actual)The suggestion to encode order of parameters in the name is not scalable - it works in isolation, but would degrate quickly with real API when you need to do all kind of assertions:

assertExpectesIsGreaterOrEqualsThanActualassertActualContainsAllTheSameElementsAsExpected

The best solution java can offer is fluent API: AssertJ

assertThat(frodo.getName()).isEqualTo("Frodo");

Outside java, this problem has other solutions:

- Named parameters - In languages like Python, named parameters eliminate ambiguity:

assertEquals(expected = something, actual = actual)

- Macros - In Rust, macros like assert_eq! automatically capture and display argument details, making order irrelevant:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[test] fn test_string_eq() { let expected = String::from("hello"); let actual = String::from("world"); assert_eq!(expected, actual); // Error message: // thread 'test_string_eq' panicked at: // assertion `left == right` failed // left: "hello" // right: "world" // at src/main.rs:17:5 } }

Have No Side Effects

Clean Code introduces side effects in a somewhat casual terms:

To make it more formal: a side effect is any operation that:

- Modifies state outside the function's scope

- Interacts with the external world (I/O, network, database)

- Relies on non-deterministic behavior (e.g., random number generation, system clock)

- Throws exception (which can alter the program's control flow in unexpected ways)

Pure functions—those without side effects—are easier to reason about, test, and reuse. Like mathematical functions, they produce the same outputs given the same inputs, with no hidden interactions.

Martin's example misses critical issues:

public class UserValidator {

private Cryptographer cryptographer;

public boolean checkPassword(String userName, String password) {

User user = UserGateway.findByName(userName);

if (user != User.NULL) {

String codedPhrase = user.getPhraseEncodedByPassword();

String phrase = cryptographer.decrypt(codedPhrase, password);

if ("Valid Password".equals(phrase)) {

Session.initialize();

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

}

"The side effect is the call to Session.initialize(), of course. The checkPassword function, by its name, says that it checks the password."

He focuses on Session.initialize() as the side effect, suggesting a rename to checkPasswordAndInitializeSession. But this misses deeper problems:

UserGateway.findByName(userName)is likely a database call - another side effect. This creates temporal coupling: authentication fails if the database is unavailable.UserGatewayis a singleton - a global implicit dependency.

This illustrates why formal understanding of side effects matters.

It also reveals a contradiction: Martin's advice to move input arguments to object fields creates side effects by definition - methods must mutate shared state.

In rewrite suggestion from chapter 2, all new methods have a side effect - they mutate fields - Modify "state outside the function's scope":

private void printGuessStatistics(char candidate,

int count) {

String number;

String verb;

String pluralModifier;

if (count == 0) {

number = "no";

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

} else if (count == 1) {

number = "1";

verb = "is";

pluralModifier = "";

} else {

number = Integer.toString(count);

verb = "are";

pluralModifier = "s";

}

String guessMessage = String.format(

"There %s %s %s%s", verb, number,

candidate, pluralModifier

);

►print(guessMessage);Interracts with the outside world - prints to STD-IO

}public class GuessStatisticsMessage {

private String number;

private String verb;

private String pluralModifier;

public String make(char candidate, int count) {

►createPluralDependentMessageParts(count);Calling a function with side effects spreads those effects to the caller