Let's get started.

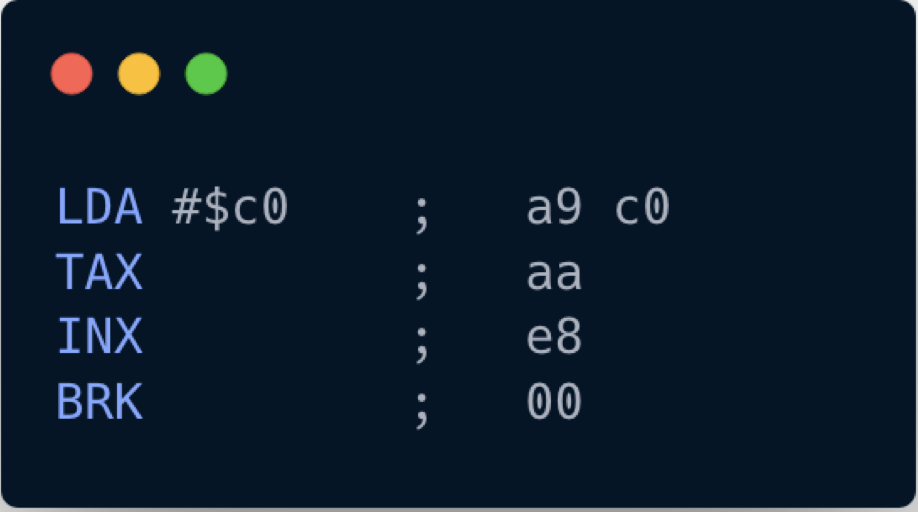

Let's try to interpret our first program. The program looks like this:

a9 c0 aa e8 00

This is somewhat cryptic as it isn't designed to be read by humans. We can decipher what's going on more easily if we represent the program in assembly code:

Now it's more readable: it consists of 4 instructions, and the first instruction has a parameter.

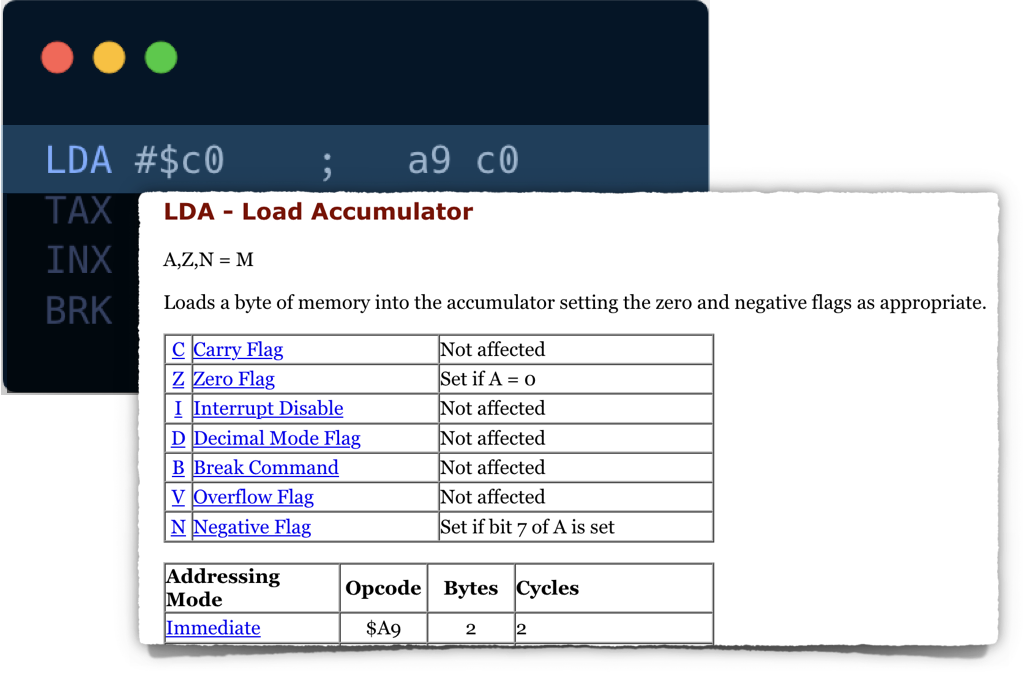

Let's interpret what's going on by referencing the opcodes from the 6502 Instruction Reference

It looks like that the command loads a hexadecimal value 0xC0 into the accumulator CPU register. It also has to update some bits in Processor Status register P (namely, bit 1 - Zero Flag and bit 7 - Negative Flag).

LDA spec shows that the opcode 0xA9 has one parameter. The instruction size is 2 bytes: one byte is for operation code itself (standard for all NES CPU opcodes), and the other is for a parameter.

NES Opcodes can have no explicit parameters or one explicit parameter. For some operations, the explicit parameter can take 2 bytes. And in that case, the machine instruction would occupy 3 bytes.

It is worth mentioning that some operations use CPU registers as implicit parameters.

Let's sketch out how our CPU might look like from a high-level perspective:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct CPU { pub register_a: u8, pub status: u8, pub program_counter: u16, } impl CPU { pub fn new() -> Self { CPU { register_a: 0, status: 0, program_counter: 0, } } pub fn interpret(&mut self, program: Vec<u8>) { todo!("") } } }

Note that we introduced a program counter register that will help us track our current position in the program. Also, note that the interpret method takes a mutable reference to self as we know that we will need to modify register_a during the execution.

The CPU works in a constant cycle:

- Fetch next execution instruction from the instruction memory

- Decode the instruction

- Execute the Instruction

- Repeat the cycle

Lets try to codify exactly that:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn interpret(&mut self, program: Vec<u8>) { self.program_counter = 0; loop { let opscode = program[self.program_counter as usize]; self.program_counter += 1; match opscode { _ => todo!() } } } }

So far so good. Endless loop? Nah, it's gonna be alright. Now let's implement the LDA (0xA9) opcode:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { match opscode { 0xA9 => { let param = program[self.program_counter as usize]; self.program_counter +=1; self.register_a = param; if self.register_a == 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b0000_0010; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b1111_1101; } if self.register_a & 0b1000_0000 != 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b1000_0000; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b0111_1111; } } _ => todo!() } }

We are not doing anything crazy here, just following the spec and using rust constructs to do binary arithmetic.

It's essential to set or unset CPU flag status depending on the results.

Because of the endless loop, we won't be able to test this functionality yet. Before moving on, let's quickly implement BRK (0x00) opcode:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { match opcode { // ... 0x00 => { return; } _ => todo!() } }

Now let's write some tests:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[cfg(test)] mod test { use super::*; #[test] fn test_0xa9_lda_immediate_load_data() { let mut cpu = CPU::new(); cpu.interpret(vec![0xa9, 0x05, 0x00]); assert_eq!(cpu.register_a, 0x05); assert!(cpu.status & 0b0000_0010 == 0b00); assert!(cpu.status & 0b1000_0000 == 0); } #[test] fn test_0xa9_lda_zero_flag() { let mut cpu = CPU::new(); cpu.interpret(vec![0xa9, 0x00, 0x00]); assert!(cpu.status & 0b0000_0010 == 0b10); } } }

Do you think that's enough? What else should we check?

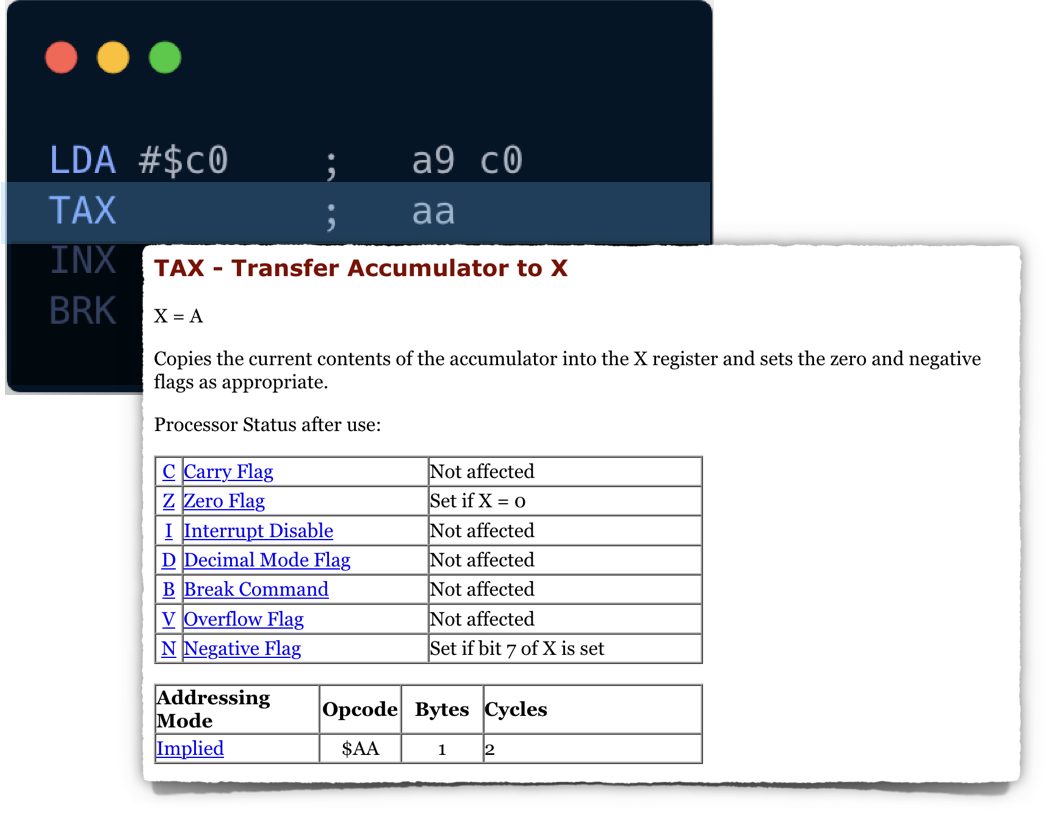

Alright. Let's try to implement another opcode, shall we?

This one is also straightforward: copy a value from A to X, and update status register.

We need to introduce register_x in our CPU struct, then we can implement the TAX (0xAA) opcode:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct CPU { //... pub register_x: u8, } impl CPU { // ... pub fn interpret(&mut self, program: Vec<u8>) { // ... match opscode { //... 0xAA => { self.register_x = self.register_a; if self.register_x == 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b0000_0010; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b1111_1101; } if self.register_x & 0b1000_0000 != 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b1000_0000; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b0111_1111; } } } } } }

Don't forget to write tests:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[test] fn test_0xaa_tax_move_a_to_x() { let mut cpu = CPU::new(); cpu.register_a = 10; cpu.interpret(vec![0xaa, 0x00]); assert_eq!(cpu.register_x, 10) } }

Before moving to the next opcode, we have to admit that our code is quite convoluted:

- the interpret method is already complicated and does multiple things

- there is a noticeable duplication between the way TAX and LDA are implemented.

Let's fix that:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // ... fn lda(&mut self, value: u8) { self.register_a = value; self.update_zero_and_negative_flags(self.register_a); } fn tax(&mut self) { self.register_x = self.register_a; self.update_zero_and_negative_flags(self.register_x); } fn update_zero_and_negative_flags(&mut self, result: u8) { if result == 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b0000_0010; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b1111_1101; } if result & 0b1000_0000 != 0 { self.status = self.status | 0b1000_0000; } else { self.status = self.status & 0b0111_1111; } } // ... pub fn interpret(&mut self, program: Vec<u8>) { // ... match opscode { 0xA9 => { let param = program[self.program_counter as usize]; self.program_counter += 1; self.lda(param); } 0xAA => self.tax(), 0x00 => return, _ => todo!(), } } } }

Ok. The code looks more manageable now. Hopefully, all tests are still passing.

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of writing tests for all of the opcodes we are implementing. The operations themselves are almost trivial, but tiny mistakes can cause unpredictable ripples in game logic.

Implementing that last opcode from the program should not be a problem, and I'll leave this exercise to you.

When you are done, these tests should pass:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[test] fn test_5_ops_working_together() { let mut cpu = CPU::new(); cpu.interpret(vec![0xa9, 0xc0, 0xaa, 0xe8, 0x00]); assert_eq!(cpu.register_x, 0xc1) } #[test] fn test_inx_overflow() { let mut cpu = CPU::new(); cpu.register_x = 0xff; cpu.interpret(vec![0xe8, 0xe8, 0x00]); assert_eq!(cpu.register_x, 1) } }

The full source code for this chapter: GitHub.