Emulating BUS

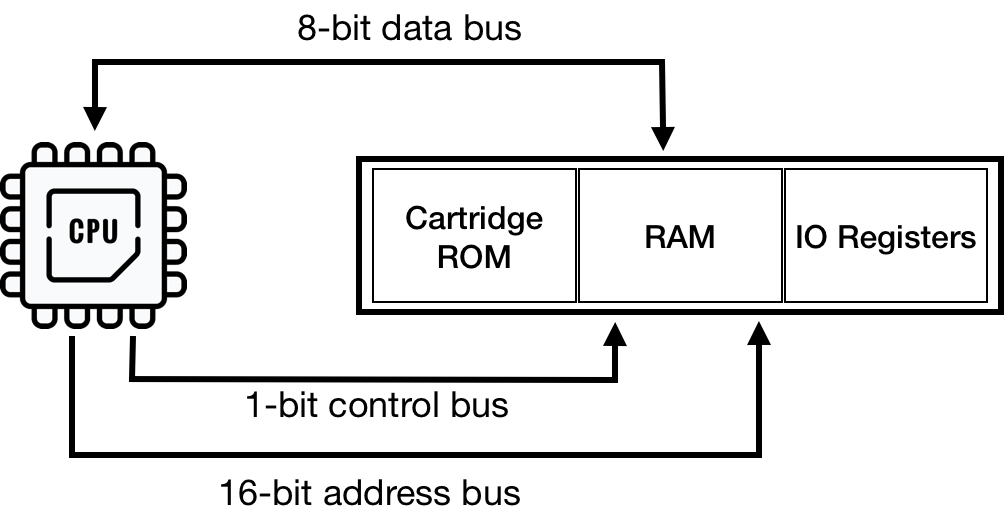

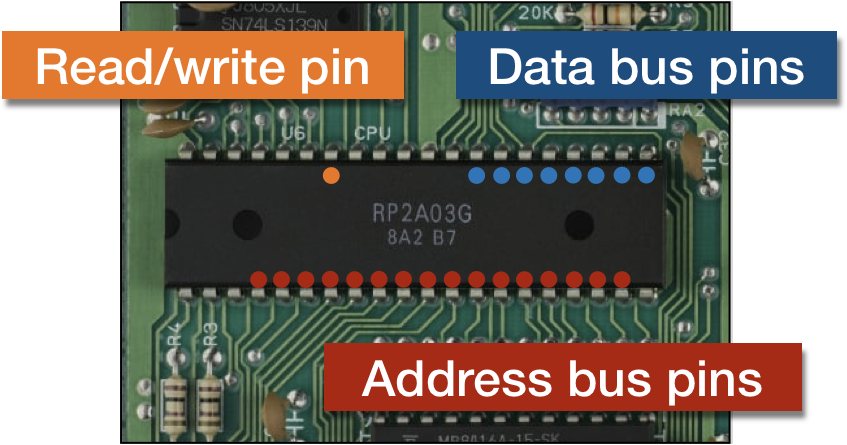

CPU gets access to memory (including memory-mapped spaces) using three buses:

- address bus carries the address of a required location

- control bus notifies if it's a read or write access

- data bus carries the byte of data being read or written

A bus itself is not a device; it's a wiring between platform components. Therefore, we don't need to implement it as an independent module as Rust allows us to "wire" the components directly. However, it's a convenient abstraction where we can offload quite a bit of responsibility to keep the CPU code cleaner.

In our current code, the CPU has direct access to RAM space, and it is oblivious to memory-mapped regions.

By introducing a Bus module, we can have a single place for:

- Intra device communication:

- Data reads/writes

- Routing hardware interrupts to CPU (more on this later)

- Handling memory mappings

- Coordinating PPU and CPU clock cycles (more on this later)

The good news is that we don't need to write a full-blown emulation of data, control, and address buses. Because it's not a hardware chip, no logic expects any specific behavior from the BUS. So we can just codify coordination and signal routing.

For now, we can implement the bare bones of it:

- Access to CPU RAM

- Mirroring

Mirroring is a side-effect of NES trying to keep things as cheap as possible. It can be seen as an address space being mapped to another address space.

For instance, on a CPU memory map RAM address space [0x000 .. 0x0800] (2 KiB) is mirrored three times:

- [0x800 .. 0x1000]

- [0x1000 .. 0x1800]

- [0x1800 .. 0x2000]

This means that there is no difference in accessing memory addresses at 0x0000 or 0x0800 or 0x1000 or 0x1800 for reads or writes.

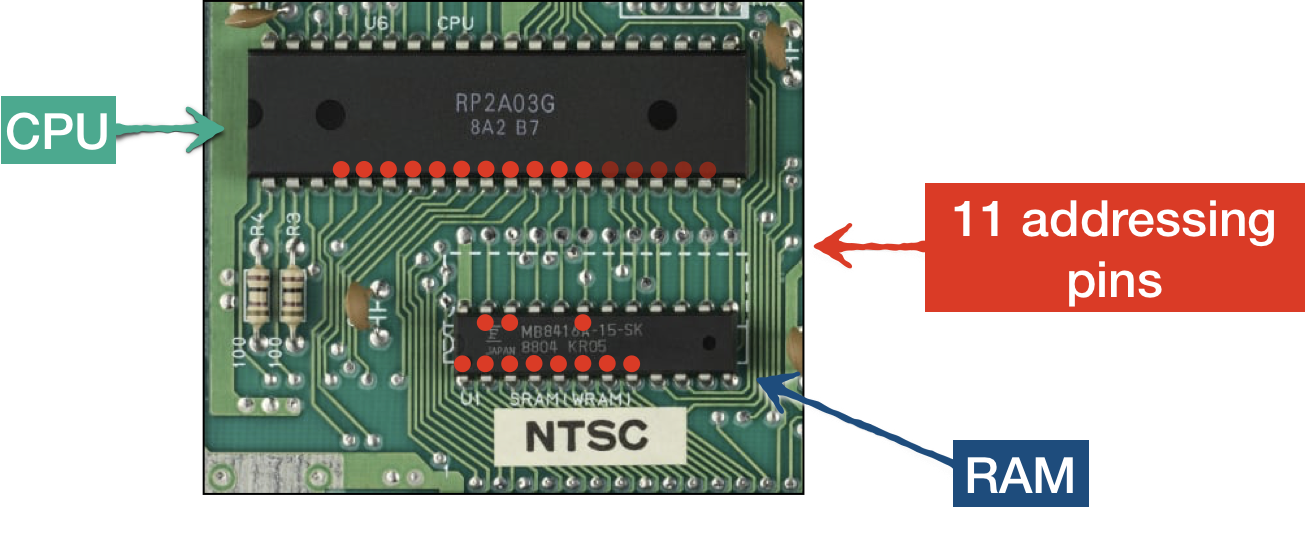

The reason for mirroring is the fact that CPU RAM has only 2 KiB of ram space, and only 11 bits is enough for addressing RAM space. Naturally, the NES motherboard had only 11 addressing tracks from CPU to RAM.

CPU however has [0x0000 - 0x2000] addressing space reserved for RAM space - and that's 13 bits. As a result, the 2 highest bits have no effect when accessing RAM. Another way of saying this, when CPU is requesting address at 0b0001_1111_1111_1111 (13 bits) the RAM chip would receive only 0b111_1111_1111 (11 bits) via the address bus.

So despite mirroring looking wasteful, it was a side-effect of the wiring, and on real hardware it cost nothing. Emulators, on the other hand, have to do extra work to provide the same behavior.

Long story short, the BUS needs to zero out the highest 2 bits if it receives a request in the range of [0x0000 … 0x2000]

Similarly address space [0x2008 .. 0x4000] mirrors memory mapping for PPU registers [0x2000 .. 0x2008]. Those are the only two mirrorings the BUS would be responsible for. Let's codify it right away, even though we don't have anything for PPU yet.

So let's introduce a new module Bus, that will have direct access to RAM.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct Bus { cpu_vram: [u8; 2048] } impl Bus { pub fn new() -> Self{ Bus { cpu_vram: [0; 2048] } } } }

The bus will also provide read/write access:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { const RAM: u16 = 0x0000; const RAM_MIRRORS_END: u16 = 0x1FFF; const PPU_REGISTERS: u16 = 0x2000; const PPU_REGISTERS_MIRRORS_END: u16 = 0x3FFF; impl Mem for Bus { fn mem_read(&self, addr: u16) -> u8 { match addr { RAM ..= RAM_MIRRORS_END => { let mirror_down_addr = addr & 0b00000111_11111111; self.cpu_vram[mirror_down_addr as usize] } PPU_REGISTERS ..= PPU_REGISTERS_MIRRORS_END => { let _mirror_down_addr = addr & 0b00100000_00000111; todo!("PPU is not supported yet") } _ => { println!("Ignoring mem access at {}", addr); 0 } } } fn mem_write(&mut self, addr: u16, data: u8) { match addr { RAM ..= RAM_MIRRORS_END => { let mirror_down_addr = addr & 0b11111111111; self.cpu_vram[mirror_down_addr as usize] = data; } PPU_REGISTERS ..= PPU_REGISTERS_MIRRORS_END => { let _mirror_down_addr = addr & 0b00100000_00000111; todo!("PPU is not supported yet"); } _ => { println!("Ignoring mem write-access at {}", addr); } } } } }

We then replace direct access to RAM from CPU with access via BUS

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct CPU { pub register_a: u8, pub register_x: u8, pub register_y: u8, pub status: CpuFlags, pub program_counter: u16, pub stack_pointer: u8, pub bus: Bus, } impl Mem for CPU { fn mem_read(&self, addr: u16) -> u8 { self.bus.mem_read(addr) } fn mem_write(&mut self, addr: u16, data: u8) { self.bus.mem_write(addr, data) } fn mem_read_u16(&self, pos: u16) -> u16 { self.bus.mem_read_u16(pos) } fn mem_write_u16(&mut self, pos: u16, data: u16) { self.bus.mem_write_u16(pos, data) } } impl CPU { pub fn new() -> Self { CPU { register_a: 0, register_x: 0, register_y: 0, stack_pointer: STACK_RESET, program_counter: 0, status: CpuFlags::from_bits_truncate(0b100100), bus: Bus::new(), } } // ... } }

If we want our unit tests to still pass, we will temporarily adjust the load function to load our test programs to the new VRAM:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn load(&mut self, program: Vec<u8>) { for i in 0..(program.len() as u16) { self.mem_write(0x0000 + i, program[i as usize]); } self.mem_write_u16(0xFFFC, 0x0000); } }

And that's pretty much it for now. Wasn't hard, right?

The full source code for this chapter: GitHub